MONTEVERDI AT THE FESTIVAL

Share

From L’Orfeo to L’Incoronazione and via Monteverdi’s madrigals and religious music, the Festival has helped give the Italian composer his rightful place in the history of opera while still affirming his profound modernness.

MONTEVERDI’S L’ORFEO: THE BEGINNINGS OF OPERA AND OF THE FESTIVAL D’AIX

While the Festival d’Aix began under the auspices of Mozart, Monteverdi was never far away. In 1950, Gabriel Dussurget programmed a “Monteverdi concert”: it was a concert version of L’Orfeo, an opera rarely seen by audiences at the time. Although the composer’s oeuvre was not exactly unknown, it was seldom performed, or was performed for limited audiences. The fact that the Festival director had many musicologists in his entourage — including Georges de Saint-Foix, who had become familiar with Monteverdi when he attended the Schola Cantorum — explains this tendency in the early years of the Festival d’Aix.

Monteverdi quickly became one of the pillars on which the Festival built its identity: he was “Latin”, “Mediterranean”, and, above all, was considered the father of opera thanks to L’Orfeo (1607): he thus had his rightful place in a festival that strived to revitalize opera and embody the genre in Provence.

L’Orfeo was first performed on stage at the Festival in the summer of 1965, in a production by the Italian dramaturge Sandro Sequi. Rather than conform to previous, historically-informed versions, the orchestra, conducted by Gianfranco Rivoli, accompanied a production that had one major objective: to bring this founding work of opera into the twentieth century.

With this same “returning-to-the-roots-of-opera” spirit, and in an effort to rebuild an institution, Stéphane Lissner programmed a “Monteverdi trilogy” when he arrived at the helm of the Festival, with L’Orfeo in 1998, L’Incoronazione di Poppea in 1999, and Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria in 2000.

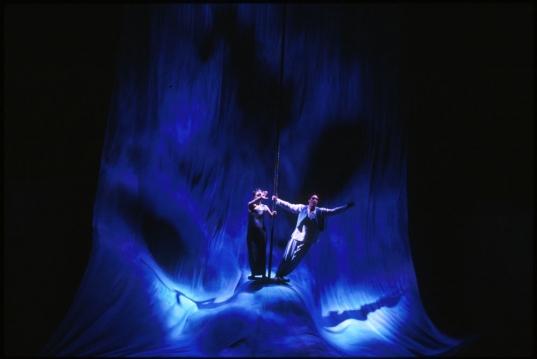

Hence, L’Orfeo was once again present at the rebirth of the Festival in 1998: it was staged by the American choreographer Trisha Brown (1936–2017), who breathed new life into the work through dance. In 1965, Sandro Sequi’s production of L’Orfeo had likewise integrated choreography, thanks to the expressionist dancer and choreographer Clotilde Sakharoff (1892–1974).

The 1998 production, conducted by René Jacobs (a Belgian singer and conductor specialised in Baroque music), was reprised in 2007 under the Festival’s general director Bernard Foccroulle, with Stéphane Degout in the role of Orpheus.

One should also note the significant role of the Académie européenne de musique in the Festival’s productions of Monteverdi’s works — as though the youth of the Academy’s singers reflect the luminous birth of the operatic genre.

RE-PREMIERES: BAROQUE OPERA UNVEILED AT AIX

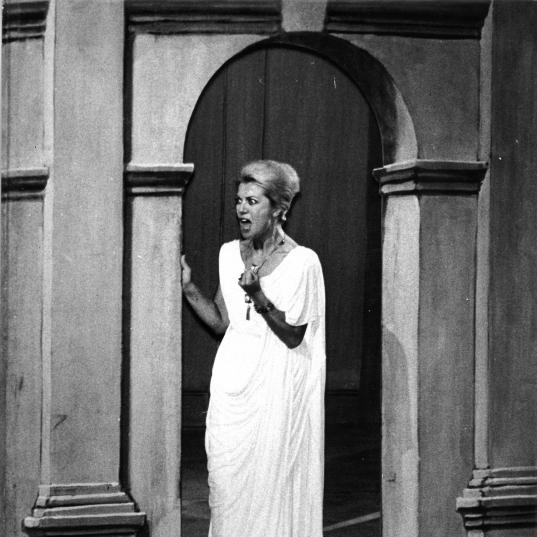

The Festival offered audiences a production of L’Incoronazione di Poppea in 1961, thereby staging one of the first productions of the work in the twentieth century. To recreate imperial Rome, Suzanne Lalique designed an ancient palace in trompe l’oeil and draped all the singers in togas.

In the pit, Bruno Bartoletti conducted a large, “classical” orchestra and great singers, commensurate with the nineteenth-century Italian operatic repertoire: Teresa Berganza (Ottavia), Robert Massard (Nerone) and Jane Rhodes (Poppea) formed a slightly anachronistic but convincing trio. The production included only one and a half of the three hours of music to which we have now become accustomed: major cuts were made and certain songs were not performed (including the celebrated final “Pur ti miro”) in Gianfranco Malipiero’s version.

While it delighted audiences, the production disappointed some music lovers and experienced musicologists. It went on tour at the “Mai de Versailles” festival in 1962, before returning to Aix in the summer of 1964.

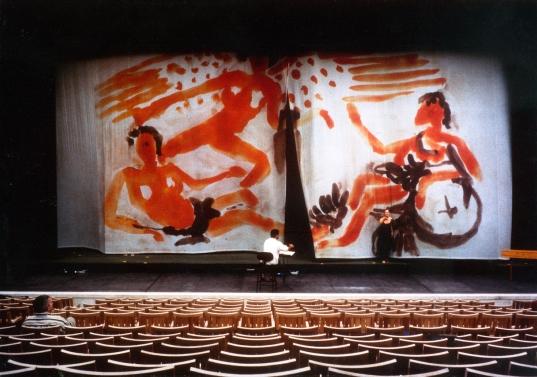

Nearly 40 years later, in 1999, a new production of L’Incoronazione di Poppea was yet another Festival milestone. Klaus Michael Grüber offered a sleek and sensual staging, with a set designed by the painter Gilles Aillaud. Tuscany pines and frescos of Pompei helped create a tableau of the Italian countryside in this meticulously-staged production with superbly directed actors.

The production was equally striking in terms of music, since it was the first opera that Marc Minkowski conducted at Aix-en-Provence. The conductor opted to use the so-called “Venice” manuscript, in which the plot is more focused around the couple formed by Nerone (Anne Sofie von Otter) and Poppea (Mireille Delunsch), and eliminates the role of the nurse. Sylvie Brunet portrayed an unsettling Ottavia alongside this couple.

Without including a “Baroque” orchestra, Marc Minkowski greatly enhanced the part of continuo (the instruments that play basso continuo in Baroque music) and offered a score full of éclat. The production was a great success and was reprised in 2000.

Finally, in 2000, as part of its ongoing commitment to introducing lesser-known works, the Festival programmed a production of Ritorno d’Ulisse in patria by the Académie européenne de musique, as the culmination of its vocal residency that same year.

MADRIGALS AND STAGING: THE FESTIVAL AS A CENTRE FOR EXPERIMENTATION

As of the 1960s, the Festival d’Aix offered staged versions of Monteverdi’s madrigals. The performances were conceived of as veritable demonstrations: they aimed to prove that the madrigal is one of the sources of opera and yet is intrinsically modern, through its minimalist means and its unprecedented emotional expression.

Among Monteverdi’s vast number of madrigals, the eighth book is a focal point: Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda in particular attracted the attention of Festival programmers and of stage directors.

In 1961, the Festival offered a choreographed version of Combattimento, in which two stars of the Opéra de Paris, Claude Bessy and Attilio Labis, portrayed the dancing doubles of Jane Berbié and Luigi Alva. In 1967, this scena from Madrigali guerrieri et amorosi (i.e. the eighth book of madrigals) was staged once again by a dancer: Pierre Lacotte, alongside set designer François Ganeau, organised an evening around Combattimento, “under the green vault of plane trees in Le Tholonet”, for a single performance on 26 July 1967.

In these versions, focus was placed on dance; for, as it is known, Court galas consisted of true festive balls, which were integrated into Monteverdi’s dramatic works.

In 1970, there was a new attempt at recreating the supposed ambiance of the Court of Mantua in the early seventeenth century. With its period costumes and Baroque dances, Sandro Sequi’s production, performed in the courtyard of the Palais de l’Archevé (which mirrored the palace of Mantua), made the Festival d’Aix a new birthplace for opera.

In 1999, Stéphane Lissner put together another “evening of madrigals” at the Hôtel Maynier d’Oppède, with a programme structured around Cena Furiosa, in a true musical banquet staged by Ingrid von Wantoch Rekowski and conducted by Marc Minkowski.

These madrigal-based stagings have always been one of the specialities of the Festival d’Aix, and have revealed Monteverdi’s madrigal work to be a linchpin in his overall oeuvre and a turning point in the history of opera. The productions performed at the Théâtre de l’Archevêché and the Théâtre du Jeu de Paume honoured these works as opera productions in their own right.

MONTEVERDI: A BRIDGE BETWEEN EARLY AND CONTEMPORARY MUSIC

Through all of the productions and concerts of Monteverdi’s work that it has offered, the Festival d’Aix has been an educational space for his oeuvre.

It also helped develop a discourse around Monteverdi, by identifying him both as the first link in a chain of great figures in opera — and thereby connecting him to Lully, Mozart and Wagner — and as the founder of the modern language of music. This double definition is an essential part of the Festival’s identity as well.

In the programme of the 1967 Festival, you could read this tribute by Claude Rostand for the 400th anniversary of Monteverdi’ birth: “The soul of the Festival d’Aix is opera. And it was only fitting that this festival should aim to honour with constancy, regularity and diversity the creator of opera, the one who, by inventing the genre, and bringing it from the threshold of lyrical history to its most complete point of perfection, solved, in advance and at a single stroke, all the technical and expressive problems on which its most ingenious or brilliant successors would then work, or even stumble, throughout the centuries.”

The Festival has often created a dialogue between Monteverdi’s oeuvre and that of contemporary composers, as in its 1983 edition: Ian Strasfogel’s production of Il Combattimento was preceded by Lucianno Berio’s production of Passaggio (1963). This French premiere of a messa in scena for soprano, double chorus and orchestra — a reflection on the genre of opera, on singing and on dramaturgy — echoes the experimentation carried out by Monteverdi four centuries earlier.

PERFORMANCES: SPECIALISING IN BAROQUE MUSIC

A long series of ensembles specialised in Monteverdi’s work have performed at Aix — in concerts, operas and staged madrigals — and the tendency has accelerated since the 1980s, including René Jacobs, the Arts Florissants conducted by William Christie, and, this year, Leonardo García Alarcón’s ensemble Cappella Mediterranea.

The Festival also programmes concerts of Monteverdi’s religious music, often performed by the same musical groups that are specialised in Baroque repertoires.

In 1965, the Princeton Choir came to Aix to perform Selva Morale e spirituale (1641), a collection of 40 religious pieces that are closely related to Monteverdi’s non-religious music. Then on 22 July 1992, Les Arts Florissants performed fragments of the same Selva morale e spirituale at the Cathédrale Saint-Sauveur.

Anne Le Berre